Introduction

Over the past few weeks I’ve been digging into a small, self-contained map matcher written in Go. The goal was simple: explore whether it’s possible to build a lightweight Hidden Markov Model (HMM) map matching service that doesn’t rely on external routing engines, yet still handles high concurrency and good throughput for short GPS traces.

The use case I had in mind is one where a service might need to process many short GPS traces (think under 5 minutes and only a few miles), at high volume (think on the order of hundreds of thousands per hour) and do so with minimal infrastructure fuss.

The prototype lives here: https://github.com/kuanb/gorouter

What the Router Does

You start the router like this:

go run ./cmd/router -pbf district-of-columbia-251222.osm.pbf

On launch it parses the specified OSM PBF, builds an in-memory road graph, indexes road segments with an R-tree, and exposes a simple HTTP endpoint for map matching.

Each incoming trace is matched using a straightforward HMM approach:

-

It finds nearby segment candidates using the spatial index.

-

It scores emission likelihoods based on distance.

-

It scores transitions using graph connectivity and simple heuristics.

-

It runs a Viterbi pass over the sequence to find the most likely path.

This isn’t a full routing engine (it doesn’t do traffic modeling or turn penalties, for example) but for short traces it gets the job done.

Go and Concurrency: Reasoning for Language Selection

One of the reasons this project feels “Go-ish” is that concurrency comes almost for free with the standard library. The router uses Go’s built-in HTTP server, and each request is already handled in its own goroutine by default.

Here’s the core HTTP handler:

http.HandleFunc("/match", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

result, err := matcher.Match(r.Context(), trace)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(result)

})

There’s no worker pool or thread scheduler in user code: Go’s net/http does the heavy lifting. The shared graph and spatial index are read-only after initialization, and per-request state is short-lived. That pattern maps well to workloads where requests are independent and bursts are expected.

Libraries for Spatial Indexing and Geospatial Work

One area where I had more hesitation than usual was around geospatial libraries. My familiarity with Go’s geospatial ecosystem is at this time limited, going into this project.

For spatial indexing, I used github.com/tidwall/rtree, which provides a simple in-memory R-tree implementation. That underpins the nearest-neighbor lookups used to find candidate road segments for each GPS point. I also used github.com/tidwall/geoindex, which wraps common spatial indexing patterns in a slightly higher-level API. Together, these handled the core spatial lookup needs without introducing much complexity.

For geometry primitives and distance calculations, I relied on github.com/paulmach/orb. Orb provides clean representations for points and line strings and enough geometric operations to avoid reinventing basic math, while still being easy to reason about.

For OpenStreetMap ingestion, I used github.com/qedus/osmpbf to parse PBF files and stream OSM primitives into my own graph structures.

Just thinking out loud: I was initially uneasy building this on top of libraries with only a few hundred stars. In ecosystems like Python, geospatial tooling tends to be backed by much larger and more established communities. Go’s geo ecosystem feels smaller and more fragmented, and there isn’t an obvious “standard” stack. It could also just be me being naive, though.

That said, once I read through the source of the libraries I was considering, I felt comfortable moving forward. The code is small, readable, and fairly direct. There’s very little abstraction or magic, which made it easier to reason about correctness and performance.

Tradeoffs I also wonder about: The ecosystem is clearly smaller, but it’s also a pragmatic and composable language. For this project, assembling a solution from a handful of focused building blocks ended up being a reasonable tradeoff.

Load Testing

To get a sense of performance, I wrote a small Python harness that sends concurrent requests against a locally running router and measures throughput and latency.

I ran it locally on a MacBook Pro (M2, 32 GB RAM) with a Washington, DC PBF. The test sent 10,000 total requests with about ~250 concurrent in-flight requests.

Here are the results:

Total routes: 10000

Successful: 10000 (100%)

Total time: 34.29s

Throughput: ~291.6 routes/sec

Median latency: ~294ms

P95 latency: ~913ms

P99 latency: ~980ms

A few things jump out. Throughput stays close to ~300 requests per second, the median latency is under 300 ms even under load, and tail latencies sit below a second without any tuning. For a small, single-process prototype, that’s a solid baseline.

Batch Size and Concurrency Observations

I also experimented with the effect of batch size on throughput and latency. Using the same 10,000-route test set, I compared three scenarios: high concurrency with 250 in-flight requests, moderate concurrency with batch size 100, and effectively no concurrency with batch size 1.

Two interesting results stood out:

Batch Size 100

Total routes: 10000

Successful: 10000 (100%)

Total time: 32.62s

Throughput: 306.6 routes/sec

Median latency: 102.8ms

P95 latency: 494.0ms

P99 latency: 537.1ms

With a moderate batch size, throughput improved slightly over the earlier 250-concurrency test. Median latency dropped to ~103ms, although tail latency (P95/P99) remained near half a second.

Batch Size 1 (No Concurrency)

Total routes: 10000

Successful: 10000 (100%)

Total time: 47.38s

Throughput: 211.05 routes/sec

Median latency: 3.0ms

P95 latency: 4.8ms

P99 latency: 6.0ms

Processing requests sequentially drastically reduces per-request latency. Each individual match is extremely fast - single-digit milliseconds - but overall throughput suffers: the total run time increases because requests are not processed in parallel.

Implications

For a high-volume service like the one this router is targeting, moderate concurrency (e.g., batch sizes of 100–250) hits a sweet spot: high aggregate throughput while keeping most latencies under 0.5s. The results also suggest that for very small traces, the core matching algorithm itself is extremely fast; the limiting factor for throughput is mostly concurrency management and resource contention rather than the algorithm. I would need to look into how to manage concurrency in Go – potentially limiting additional requests from being processed (so some queueing mechanism).

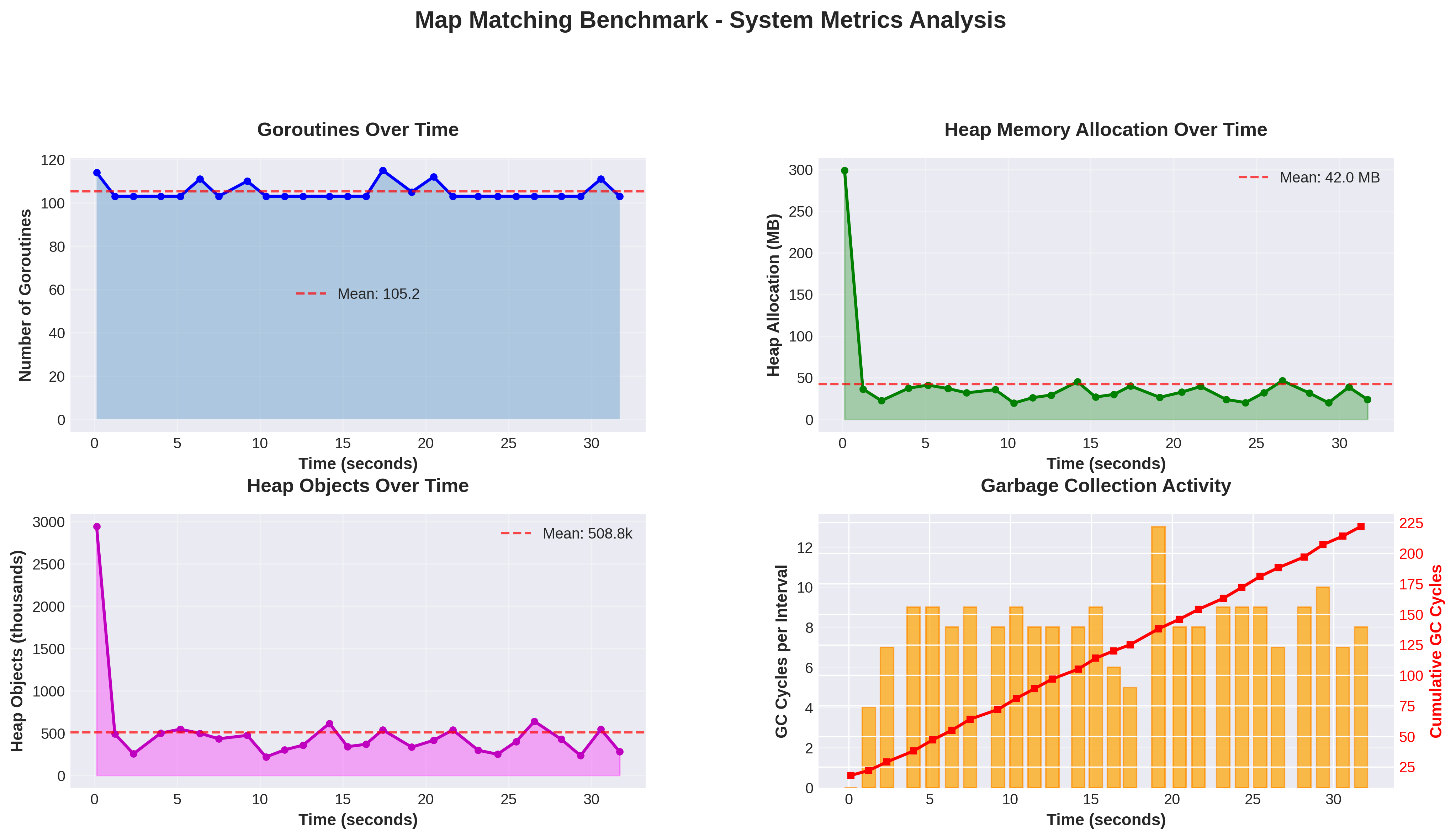

I added a metrics health-checker to the benchmarking logic to hit a background metrics endpoint to track the following stats:

| Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| goroutines | Current number of goroutines |

| alloc_mb | Currently allocated heap memory |

| sys_mb | Total memory obtained from OS |

| heap_objects | Number of allocated heap objects |

| num_gc | Number of completed GC cycles |

Re-running our benchmarker with this new metrics health-checker and a “sweet-spot” concurrency of 200:

python benchmark_mapmatch.py synthetic_routes.geojsonl --batch-size 200 --metrics-output benchmark

With this, I was able to track a few internal metrics while running the benchmarks to get a sense of memory usage, goroutine count, and garbage collection behavior. Summary results were as follows:

Server Metrics Summary

Collection duration: 31.7s

Samples collected: 26

Memory (Allocated MB):

Min: 19.48 MB

Max: 299.10 MB

Mean: 41.99 MB

Goroutines:

Min: 103

Max: 115

Mean: 105.2

General observations from the results:

-

Memory usage is modest. Even at peak, the router allocated ~300MB (upon the initial request, it immediately dropped down to the about the median). The average was around 42MB. This confirms that the in-memory graph and R-tree are lightweight.

-

Goroutine count stays predictable. Between 103–115 goroutines, the server handles concurrency without spawning excessive threads. Most of these goroutines might also be the HTTP server, worker routines, and GC activity.

-

Garbage collection is frequent but cheap. 204 GC cycles occurred during the ~32s benchmark, reflecting the allocation and deallocation of per-request state. The low impact on throughput and latency suggests that Go’s GC handles this workload efficiently.

Overall, these internal metrics reinforce the earlier observations: the router is lightweight, scales with concurrency, and does not impose significant memory or GC overhead under realistic load.

Back-of-the-Envelope Capacity

At roughly 292 requests per second, a single instance translates to:

-

~17,500 requests per minute

-

~1 million requests per hour

In practice, it’s safer to discount this a bit. Larger graphs, cloud overhead, and garbage collection will all eat into headroom. Even with a conservative estimate of ~10k requests per minute per instance, we can start to think about what it takes to reach very high throughput.

If the target is 250k requests per minute, then:

250,000 / 10,000 ≈ 25 instances

Add headroom for regional load variability, burstiness, and failure domains, and you’re likely in the ballpark of 30–40 routers. Note based on the above metrics these don’t need to be particularly beefy instance types.

Importantly, you wouldn’t load the entire continental U.S. graph into a single process. You’d partition regionally, allocating more capacity to dense metros and fewer resources to sparser areas.

Why This Matters

Just to recap why I am doing this versus using something like Valhalla or OSRM. Those tools are very mature and stable, but they’re also large, complex, and optimized for general routing tasks/very flexible.

If your workload mostly consists of short, independent traces as my use case does, then you do not need full route planning, and you want minimal dependencies and simple scaling. So in this case, a small Go service can be a very practical alternative.

Go’s standard library gives you concurrency, a production-ready HTTP server, and predictable performance characteristics out of the box. Combined with a focused HMM implementation and spatial indexing, that’s enough to solve this class of problems.

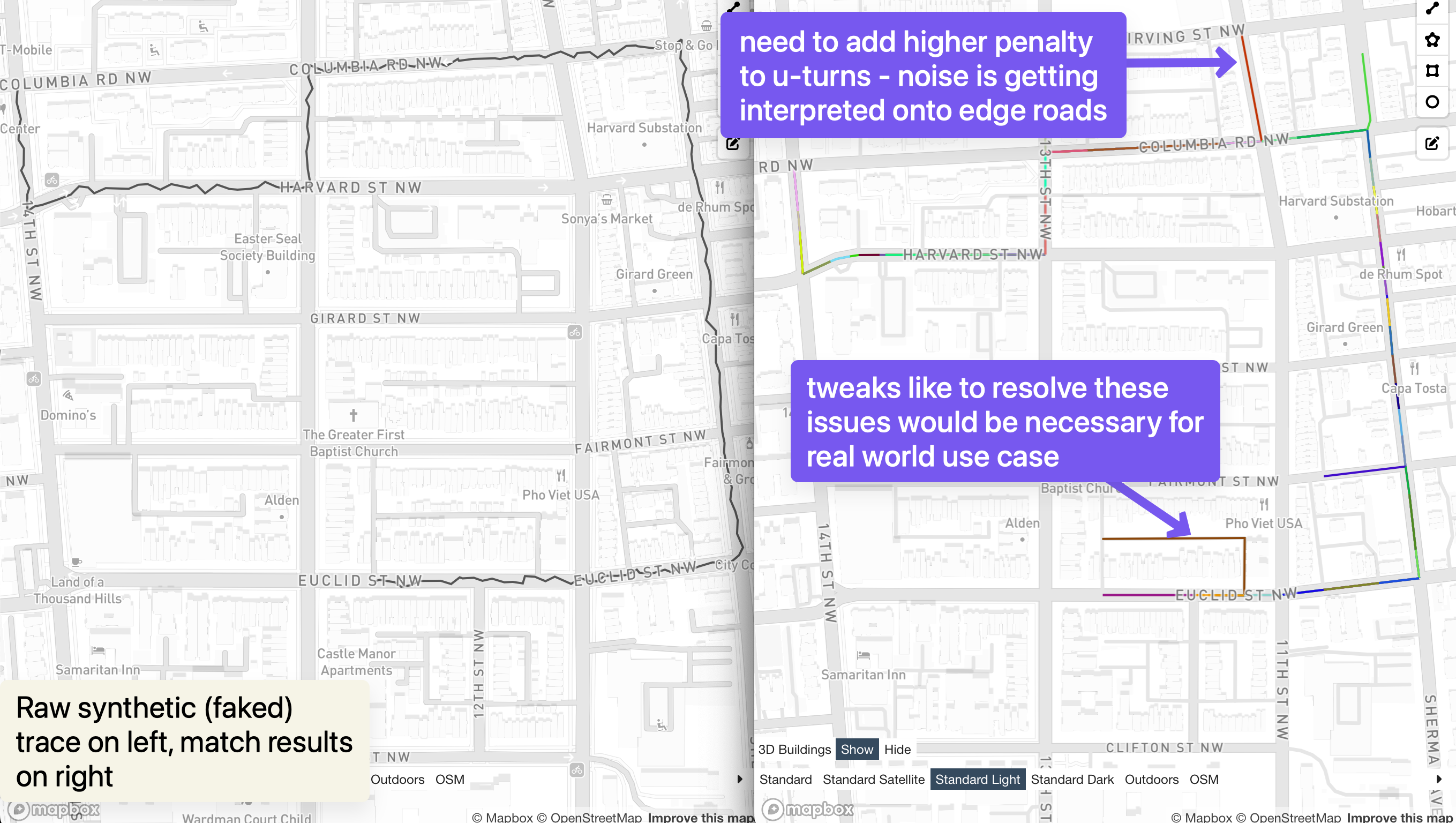

What’s Next

There’s more work to do here to flesh this out: real regional sharding, smarter batching, memory profiling, benchmarking on larger PBFs, and exploring batch matching APIs. It’s also quickly apparently the matching model needs tweaks to more strongly penalize u-turns to prevent erroneous in/out patterns for side roads when performing a map match on a road network.

But even in its current form, this prototype suggests that a lightweight, Go-based map matcher can handle serious volume when scoped appropriately. Not the Github repo may be updated after this blog post is published if I find more time to tinker on this.